In which I ask myself and y’all about the kinds of feedback you’re used to, and what you assume about feedback, structured as a series of myths I see taking shape in some of your work, and rebuttals to those ingrained impulses or tendencies.

Myth 1: Directive comments (line edits, cuts, “do this” comments made where the correction should be done) include everything that needs to be done for the essay to improve.

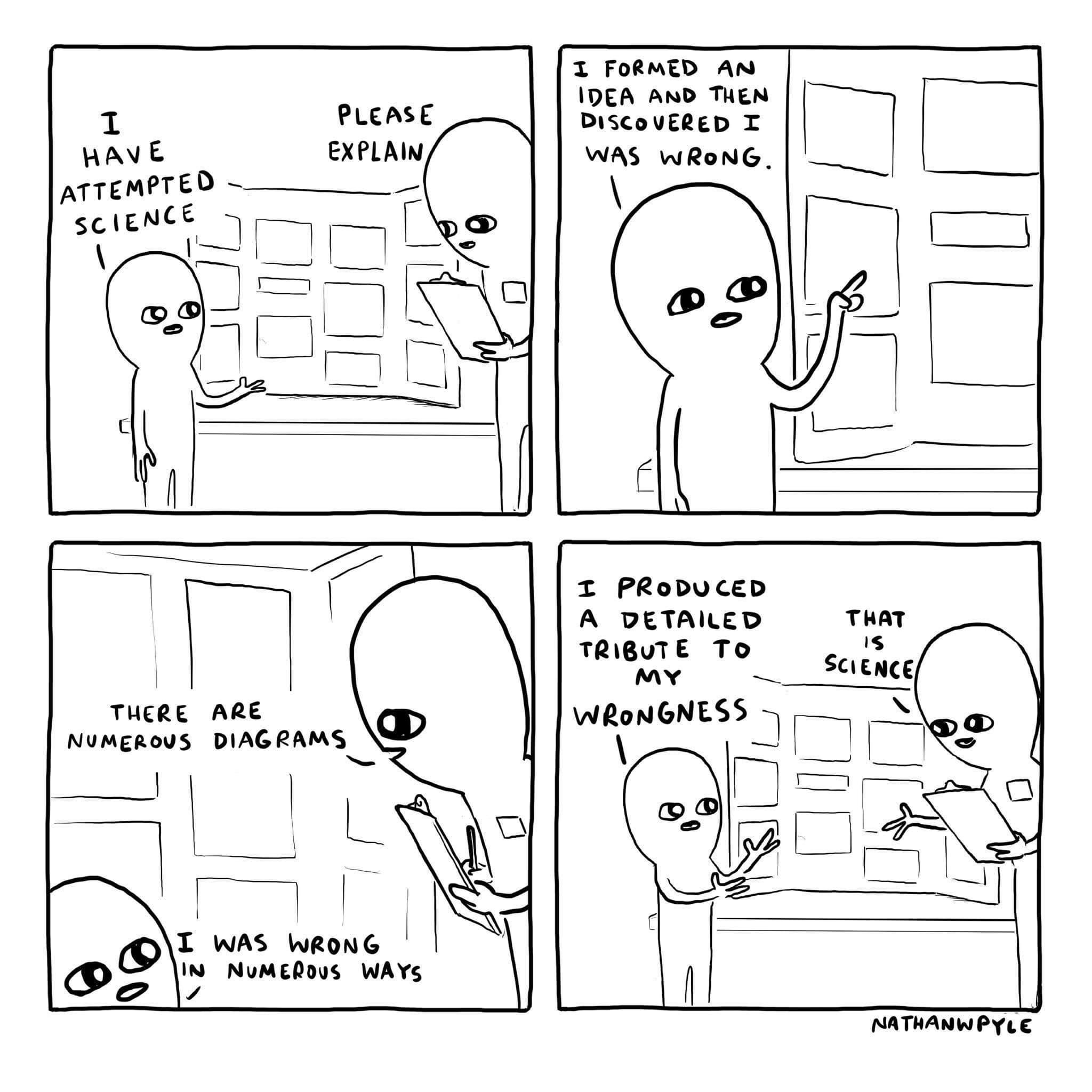

Rebuttal: It’s standard pedagogical practice to not give you step-by-step instructions on how to correct your essay, because you might end up overwhelmed with comments! Revision is a process like triage: you prioritize the substantive tasks (claims, evidence, warrants) and work up to copy-editing. Cutting all the lines for you, or providing super directive comments, teaches you how to follow instructions, not how to improve your writing. Additionally, directive comments sort of presume that you’re doing things “wrong,” and that there is a “correct” way to do it, which is a myth in and of itself.

Instead, I’ll largely post general feedback that will help us internalize how to revise, and help us locate the places in our work that need revision, without an overwhelming amount of directive comments.

Myth 2: Format, layout, and grammar are essential to do correctly and/or to the professor’s specifications during the drafting stage.

Rebuttal: Drafting always yields an initially shitty product. Good writers figure out how to write a less shitty product by practicing, imitating, adapting, failing, revising. This doesn’t come by focusing on format or layout, though admittedly layout matters–-cultural studies scholars tend to use Garamond, and composing in Comic Sans can really change how you write. I expect assignment parameters to be met, but those parameters pertain to substance, not format. Of course, we’re trained in college to do what the professor wants to get the grade, but I encourage you to focus more on doing the work in the spirit in which you’re asked to do it—fulfill the assignment but experiment in the process, and don’t be afraid to “fail up.”

Myth 3: The broader you are about your subject, the more you’ll be able to write about your subject.

Rebuttal: It may feel this way to you, at this stage in your writing career, where essays feels too long to achieve. But broadly stated topics actually give rise to more questions, and thus more pages. If I wrote “I’m studying the body modification community,” I’d have to consider tattoos, piercings, scars, amputations, prosthetic implants, corsets, and so on, and I’d have to consider how they occur everywhere, from the U.S. to Asia. I’d end up with something longer than a dissertation! So for a shorter paper, it’s actually better for me to say, “I’m studying the body modification community as exemplified by tattoo artists and aficionados at Fictional Tattoo Parlor, established in 1965 in Alphabet City in Manhattan while tattooing was still illegal in New York.”

Don’t be afraid to use “argue,” “suggest,” “indicate,” “as exemplified by,” or any synonymous transition phrases, like “as seen in,” “particularly the community of XYZ,” etc., if it helps you narrow your focus!

Here are some general strategies and formulas to consider moving forward:

- Adopting techniques from academic articles you read.

- Translating between registers: To streamline your workflow, you can “translate” from dictionary definition bullet points to sentences, identifying what words are most exemplary of the patterns emerging across the lexis, goals, and values of the community.

- Cutting repetitive or unnecessary lines: e.g., in “My exhibit is finance. I work at an investment bank on Wall Street. It’s JP Morgan,” you could revise to say, “I plan to study my experiences working at JP Morgan on Wall Street” and cut the other lines. Ask of every sentence, “Does my reader need to know this for this essay? Does the reader need to see it framed like this or differently for this essay?”

- Ask always: What does the writer know? How do they know it?

When giving feedback, it’s imperative to focus on the claim (is it answering an exploratory or interpretive question. If you can work backwards to the questions being asked, and the answers are contextualized and specific, you’re likely well on your way.

Instructions for Peer Review

An engaged form of peer review asks you to read like a reader, not an editor or professor. Consider working in a Google Doc for ease of commenting through marginalia and end notes, and for seeing how other peers in your group respond to the same piece.

Here are the general instructions:

- Share a link or file of your essay with your group members. If you’re using a Google Doc make sure you’ve enabled sharing permissions; you can use this guide if you’re not sure how to do that.

- Don’t talk about your essays! First, read without commenting.

- Read and make marginalia using the Comments feature. Underline/highlight what you think the controlling idea is, make notes about what you think the writer’s aims are, etc.

- Complete the “Essay1 Phase 1 Peer Review” Google Form posted to Canvas. (You’ll complete one form for each essay you read.) Once you hit submit, you, me, and the writer will receive a copy of your feedback as a PDF file.

- After receiving feedback via email from your peers, read what they wrote, and discuss any questions you have together as a group. You may want to ask questions about what their comments mean, how they suggest enacting those comments, collaboratively write your way towards enacting those comments, and so on.

- After workshop, write a brief reflective note (~500 words) at the end of your draft, like a short letter to me, summarizing the feedback you were given by your peers, identifying what you prioritized for revision and why, explaining which assignment parameters you think you met and which you think you need to keep striving towards. You may also reflect on the reasoning behind the decisions you made in revising your draft for submission to me: any regrets or difficulties you dealt with, your attitude towards the assignment and feedback, any burdens of college or life that crept into your work, and so on. Include this letter as a paragraph at the end of the draft you submit to me by Friday.